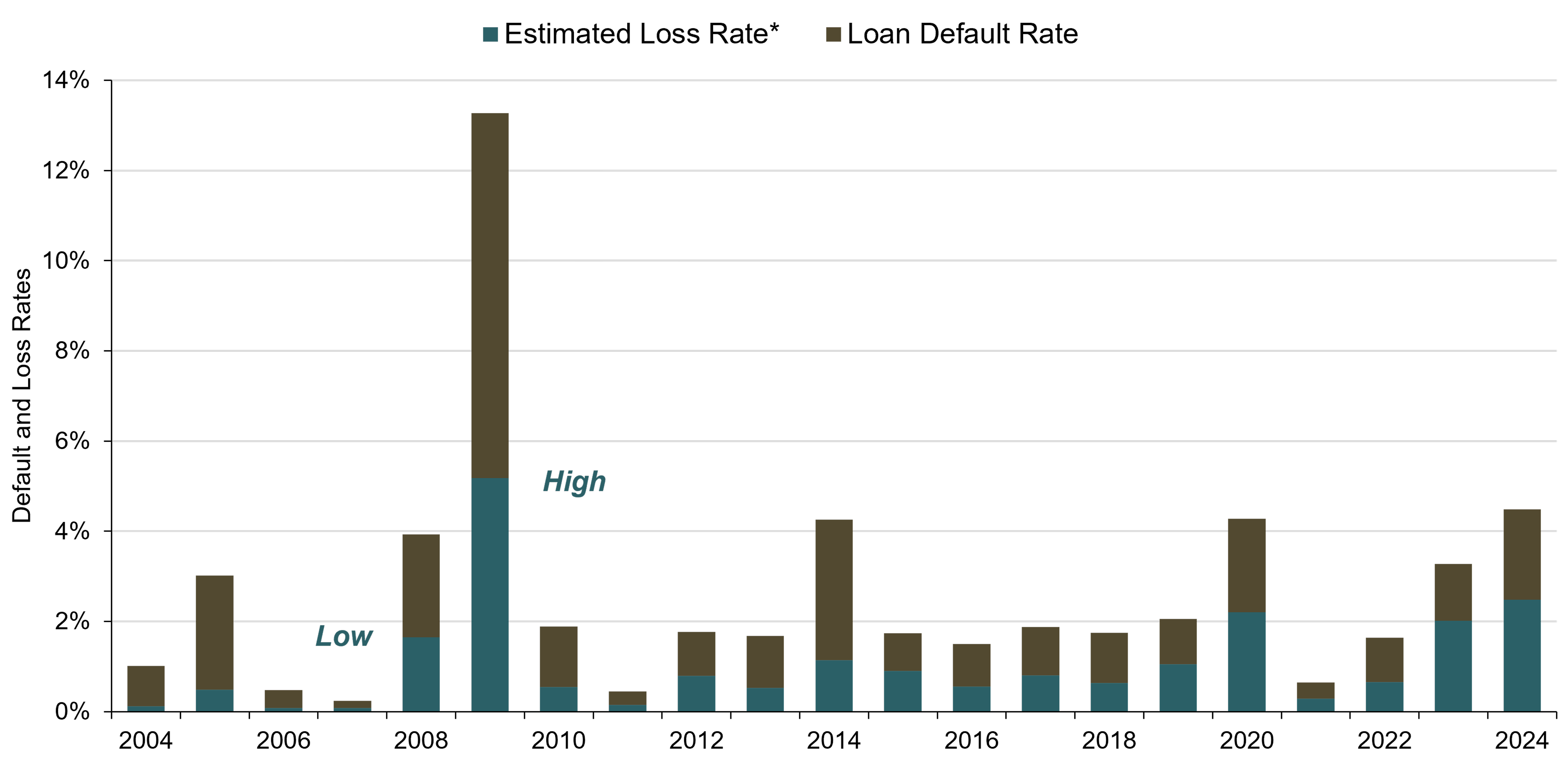

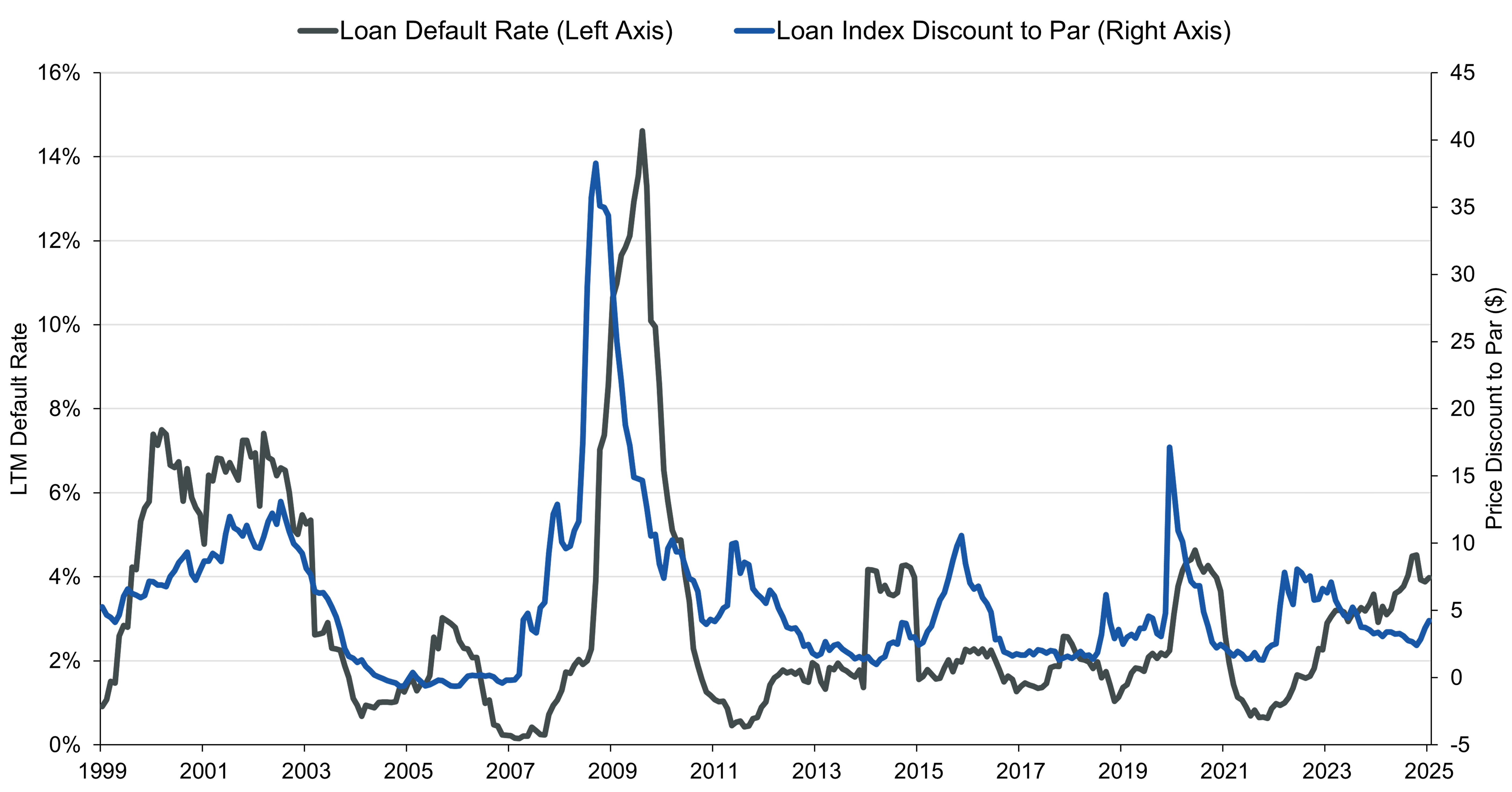

Figure 3 shows that the BSL market has historically experienced relatively low defaults and low loss severities through multiple credit cycles due to the senior and secured nature of the asset class.

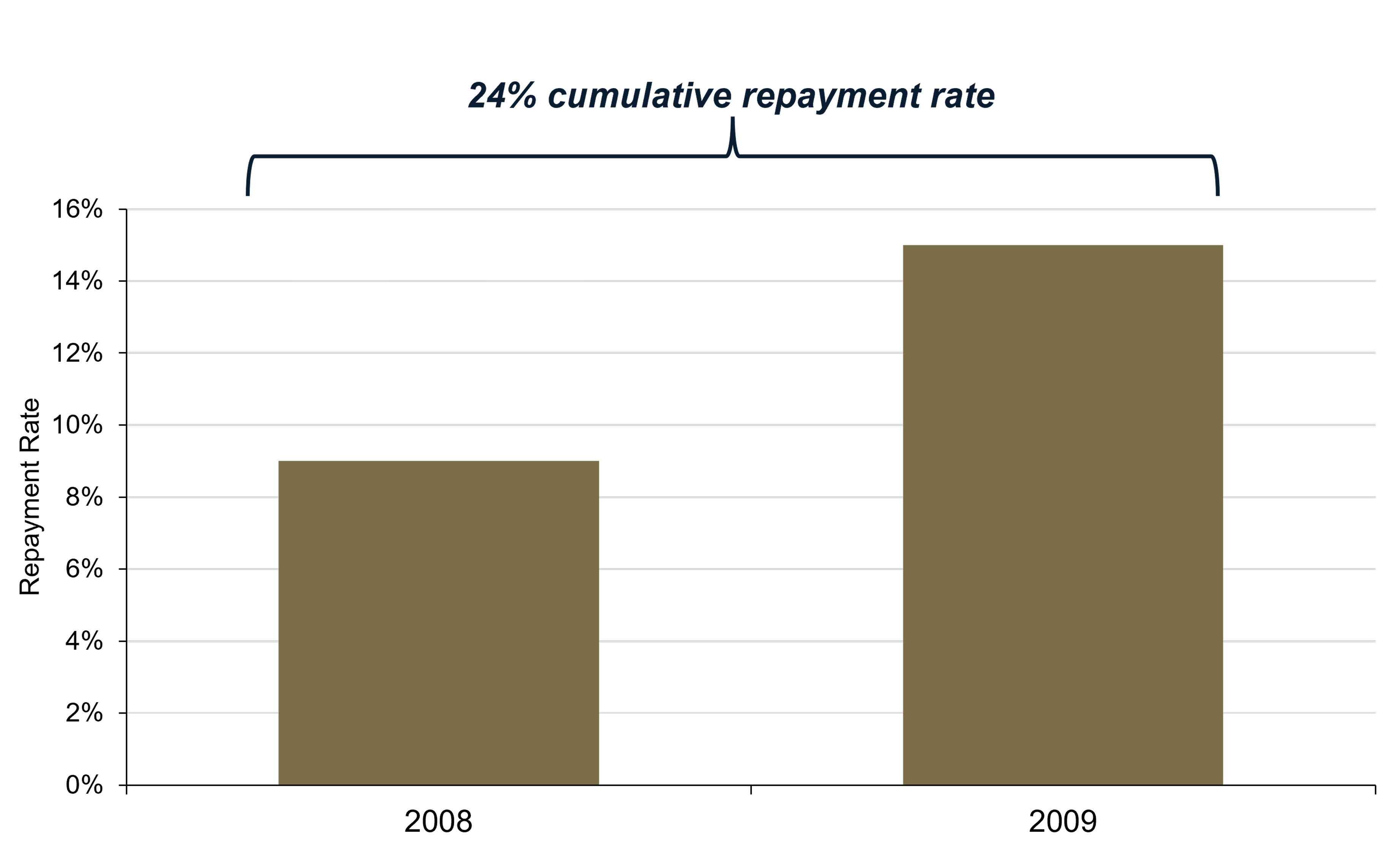

Additionally, loans are typically issued with limited call protection given to lenders, which has led to frequent prepayments prior to maturity. This feature can benefit CLO equity in weaker markets. While it may seem counterintuitive, when BSL prices are deteriorating, a portion of issuers typically still elect to pay off their loans ahead of schedule, even in the face of significant economic turmoil. This occurred during the GFC in 2008 and 2009, when almost one quarter of BSL issuers repaid their loans ahead of maturity. Because prepayments typically occur at par, this dynamic creates unencumbered capital that can be put to work by CLO managers at prevailing discounted market rates.2 During such periods of volatility, the flexibility to invest in loans at elevated spreads and discounted prices can lead to meaningful price upside as those investments mature at par or are sold at a gain. This can help to enhance returns and potentially mitigate or even overwhelm the impact of credit losses that may stem from defaults over the same period.

Structural Attributes of the CLO Vehicle

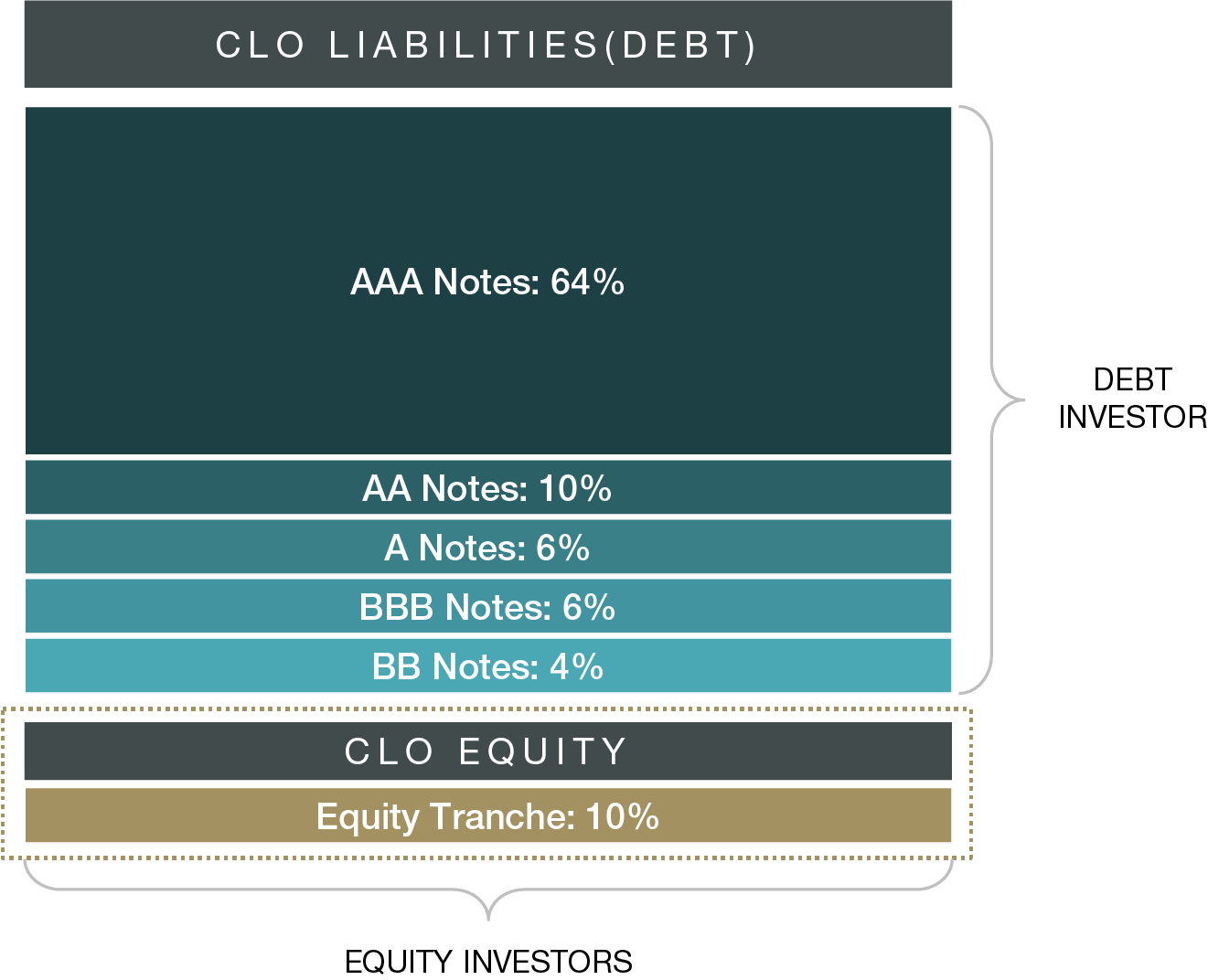

The difference between what a CLO pays to finance its debt (liabilities) and the return it receives from its BSL holdings (assets), or the arbitrage (“arb”), is at the core of what drives performance for the equity tranche investor. This spread between cost of capital on the debt and collateral return flows down the waterfall debt stack, paying each debt tranche as agreed, with excess cash flows—net of credit losses and fees—accruing to the equity investors. A typical CLO vehicle has several attributes that distinguish it from other types of waterfall securitized products. While most securitized products are limited in their ability to adapt to changing markets, CLO managers are able to actively manage both the assets (BSL collateral) and the liabilities (CLO debt tranches).

On the debt side, the manager’s cost of capital is effectively “locked in” for the life of the vehicle at the time of inception, based off the same rate (Secured Overnight Funding Rate or SOFR) as the underlying BSL collateral. It is also financed against the par value of the collateral and not subject to margin requirements based on the mark-to-market pricing of the collateral. These features are important as they provide certainty on the financing a CLO uses, which can remain in place for the life of the assets.

While the debt financing can remain in place—even if conditions in the market worsen—if financing conditions in the market improve, CLO equity holders have the option to refinance the debt largely at their discretion following a non-call period. For instance, if a CLO were to be issued during a period of wide spreads on debt, the majority equity holders retain the option to refinance at a lower spread level once things calm down, potentially locking in a lower rate that will remain until the end of the term of the CLO. The exercise of this optionality has the potential to provide attractive return benefits to the equity holder as the “arb” improves, allowing more capital to flow to the bottom of the structure.

On the asset side, CLO managers actively manage the underlying loan exposure throughout the majority of the term of the vehicle. In periods where BSL market prices decline, managers are able to take advantage of discounted loans to not only increase the yield on the collateral pool, thereby boosting the arb, but also to “build par” by buying discounted loans that will mature at par, further enhancing the potential for strong returns.

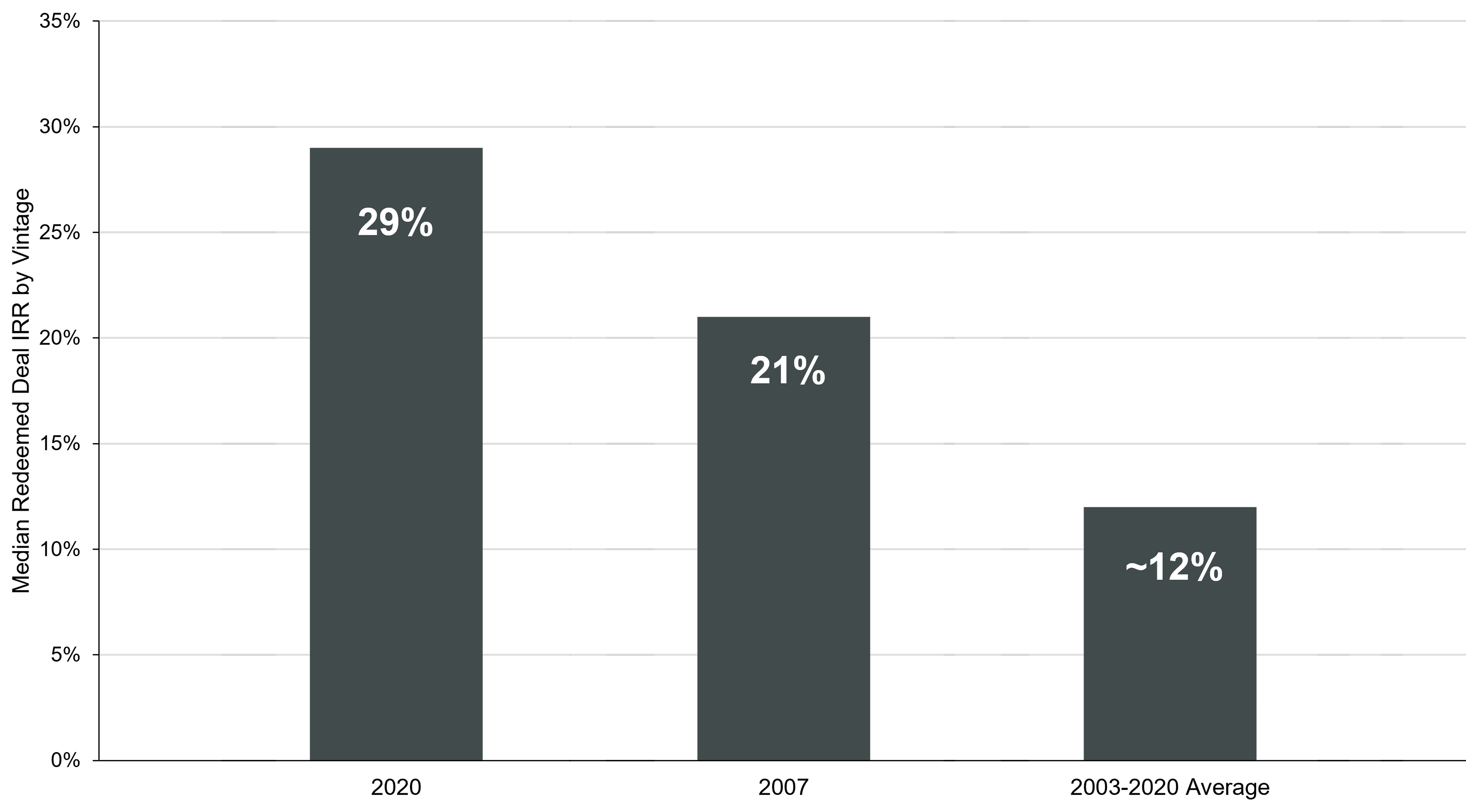

Below, we explore the two historical examples shown in Figure 2 that illustrate the active management of the liability and asset side of CLOs. While every cycle is different, we believe these illustrative examples highlight two of the main components of CLO equity performance— one case based on spread arbitrage and the other based on rapid changes in BSL collateral prices. They also illustrate that CLO equity has features that can make it resilient to many market stressors, especially for investors who can withstand changing market conditions and hold a tranche of CLO equity until the CLO is liquidated, reset, or refinanced.

Case 1: 2007 Vintage

In early 2007, CLO debt spreads were near all-time tights, which gave managers an opportunity to lock in a very low cost of capital for a multi-year period. During the financial crisis of 2008–2009, BSL prices fell significantly, spreads widened, and defaults increased. Despite mark-to-market volatility for equity investors, managers were able to reinvest early repayments (see Figure 4), maturities, and proceeds from active trading into discounted assets in the ensuing years that yielded significantly more than the manager’s low cost of capital. The result was a large distribution of excess yield for CLO equity investors who held throughout the period as the markets ultimately recovered.

It is important to note, however, that the pre-crisis vintage CLOs looked very different than the structures of today, with greater leverage and more lenient guidelines on risk-taking. While the CLO market has evolved significantly since the GFC, and current CLO deals are structured with greater levels of credit enhancement, a key advantage of the structure is the ability of a manager to lock in an attractive yield spread when the market sells off.