In his paper, “The Quality Dimension of Value Investing,” Robert Novy-Marx evaluates the importance of incorporating quality metrics into traditional value investing strategies.1 Through the lens of the investment processes of Benjamin Graham, Jeremy Grantham, Joel Greenblatt, and his own method, Novy-Marx makes the case that a quality focus, coupled with traditional value metrics and even momentum measures, can be the foundation of an effective investment strategy. This approach can potentially augment long-term returns and better distinguish “bargain stocks,” those that are undervalued based on the market’s misperception of their appreciation potential, as opposed to “value traps,” those that are cheap for a good reason.

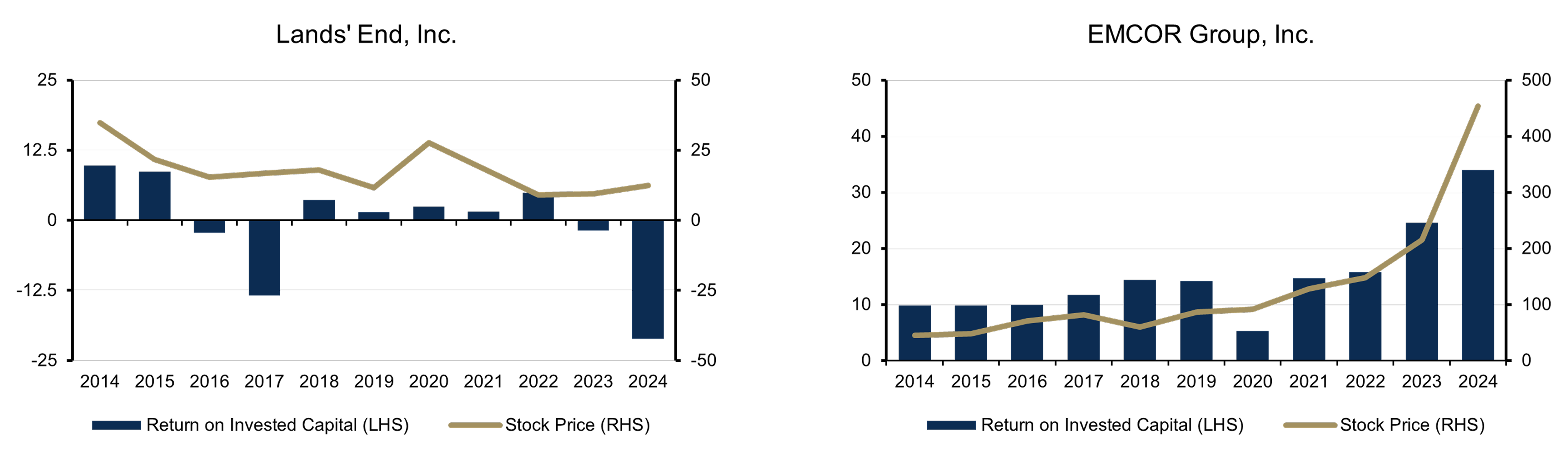

A value trap refers to a stock that appears undervalued based on traditional valuation metrics but is actually a poor investment. These stocks often attract investors with the promise of significant upside potential, only to underperform due to underlying issues such as declining business fundamentals, poor management, or adverse industry conditions.

The primary risk of value traps is that investors may hold onto these stocks for extended periods, anticipating a turnaround that never materializes. This results in capital being tied up in underperforming investments, which could have been allocated to more promising opportunities. Additionally, the persistence of negative factors can lead to further declines in stock prices, exacerbating losses and negatively impacting overall portfolio performance.

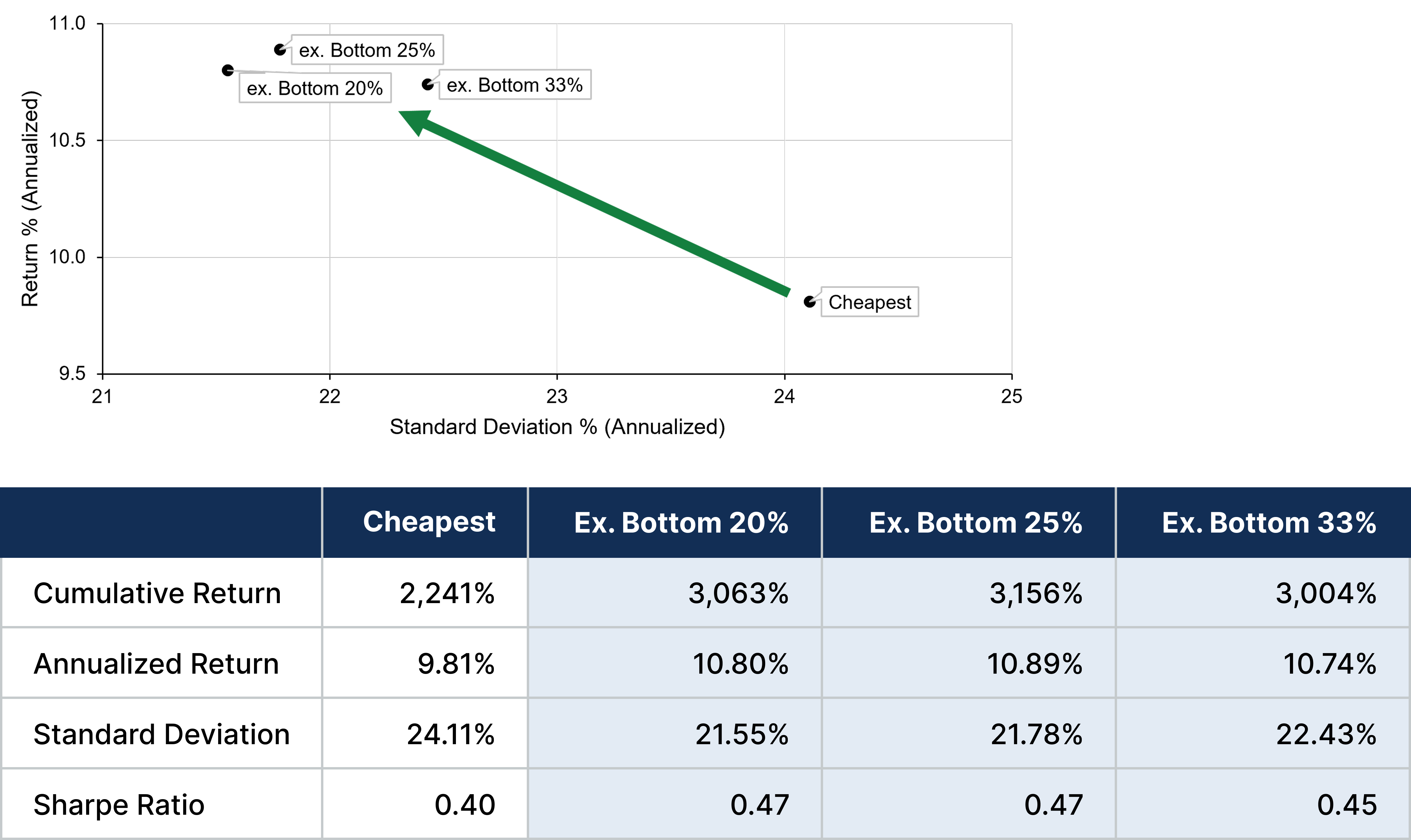

Thus, an investment strategy that can avoid selecting value traps has the potential to achieve better downside protection, by avoiding poor performing cheap stocks, and better upside capture, by putting stagnant money to work in appreciating “bargain stocks.”

Locating Value Traps

In 1992, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French released their influential research on how to define value companies, growth companies, and the high-minus-low (HML) factor, which showed, historically, how value companies had outperformed growth companies, i.e., the value premium.2 Value companies were defined as companies with lower price-to-book values (P/B), while growth companies had higher P/B ratios. When Fama and French released that data, they probably did not anticipate that over 30 years later, the evolution of the global economy would lead to asset-light businesses—those that could generate profits with less capital invested in property, plant, and equipment—displacing the status quo of traditional value investing and possibly calling the major finding of their research into question.

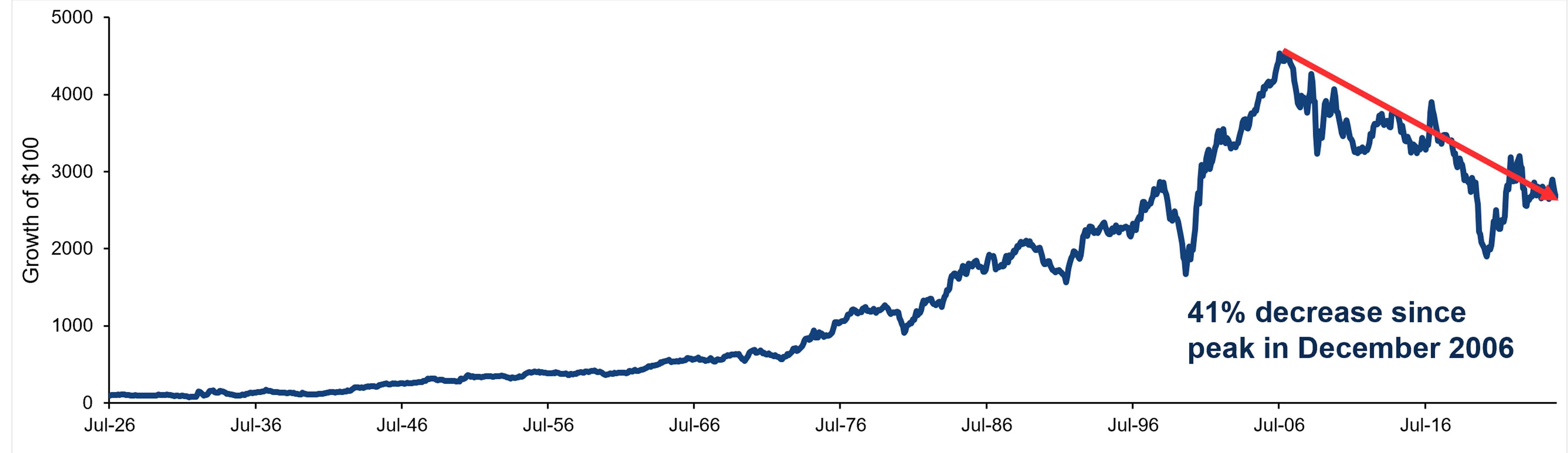

And yet, P/B is still the foundation for benchmark value style indexes such as Russell, MSCI, and Wilshire. As a result, many still utilize this formulaic approach in any value analysis. When the historical HML data was released, it showed that the value premium was a consistent method for targeting alpha. Shortly after that, cracks began to show in the outperformance, and the factor had a 40% decrease in performance from its peak in December 2006. (See Figure 1.)