We’ve written many times about the outperformance of active management over passive indexes in the fixed income space. This note will focus on exactly how managers can outperform, which approaches are repeatable and have the potential to work consistently, and which require either exceptional manager selection foresight or fortuitous timing (two things that can be difficult to distinguish even after the fact).

First, what we know: active managers commonly beat indexes. One way to show this is to look at the frequency with which the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (“Agg”) has underperformed the average active fund (defined as the 50th percentile) within each of the Morningstar U.S. Fund Intermediate Core Bond and Morningstar U.S. Fund Intermediate Core-Plus Bond categories. Based on 120 monthly observations (three-year rolling basis) over the period June 30, 2014–June 30, 2024, the Agg underperformed active core managers 70 times and active core-plus managers 86 times. That means that core managers beat the Agg nearly 60% of the time, while their core-plus counterparts outperformed over 70% of the time. (There is no assurance that this outperformance will continue in the future.)

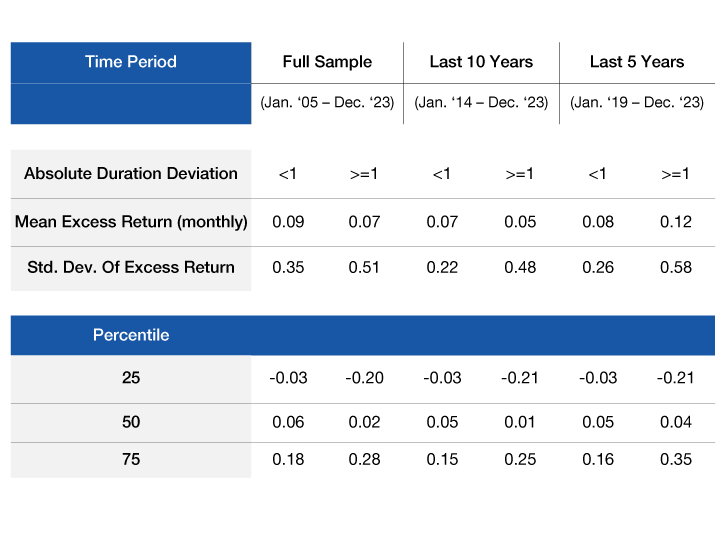

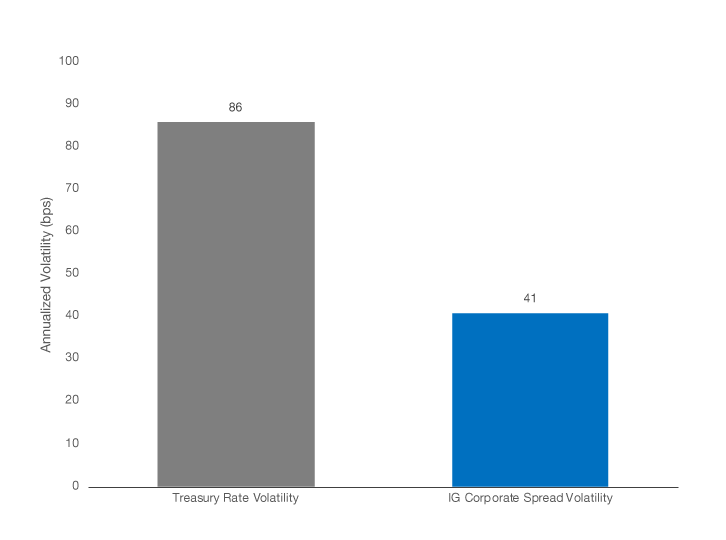

But active approaches can differ, leading to different results. Because there are two major drivers of risk in core fixed income, duration and credit, and in light of recent high-profile underperformance of large managers due to duration, we separated the return profiles of active managers in the Core category into those that have active duration positions of larger than one year (let’s call them “duration timers”) and those with positions less than one year. The impact of this categorization on subsequent monthly returns and the volatility of those returns are summarized in Figure 1 over three time periods: the full sample period going back to 2005, the last 10 years, and the last five years.

We find that, in most periods, the large duration bets did not lead to significantly larger monthly mean excess returns, and in no periods did the larger duration bets lead to higher median returns. There is a significant positive skew to the results of the duration timers, as evident in the 75th percentile manager excess performance of over 25 basis points (bps) monthly, or over 3% annually, suggesting that skill may exist but unevenly benefits a subset of managers. Further, the penalty for incorrect bets is severe, as we’ve seen in the recent experience of those high-profile mangers. The bottom 25th percentile of duration timers costs around 20 bps per month in excess return loss, or over 2% annually, compared to a modest annual 0.4% excess return loss for the bottom quartile of the limited duration timing cohort.