How Higher Rates May Reshape the Liquidity Environment

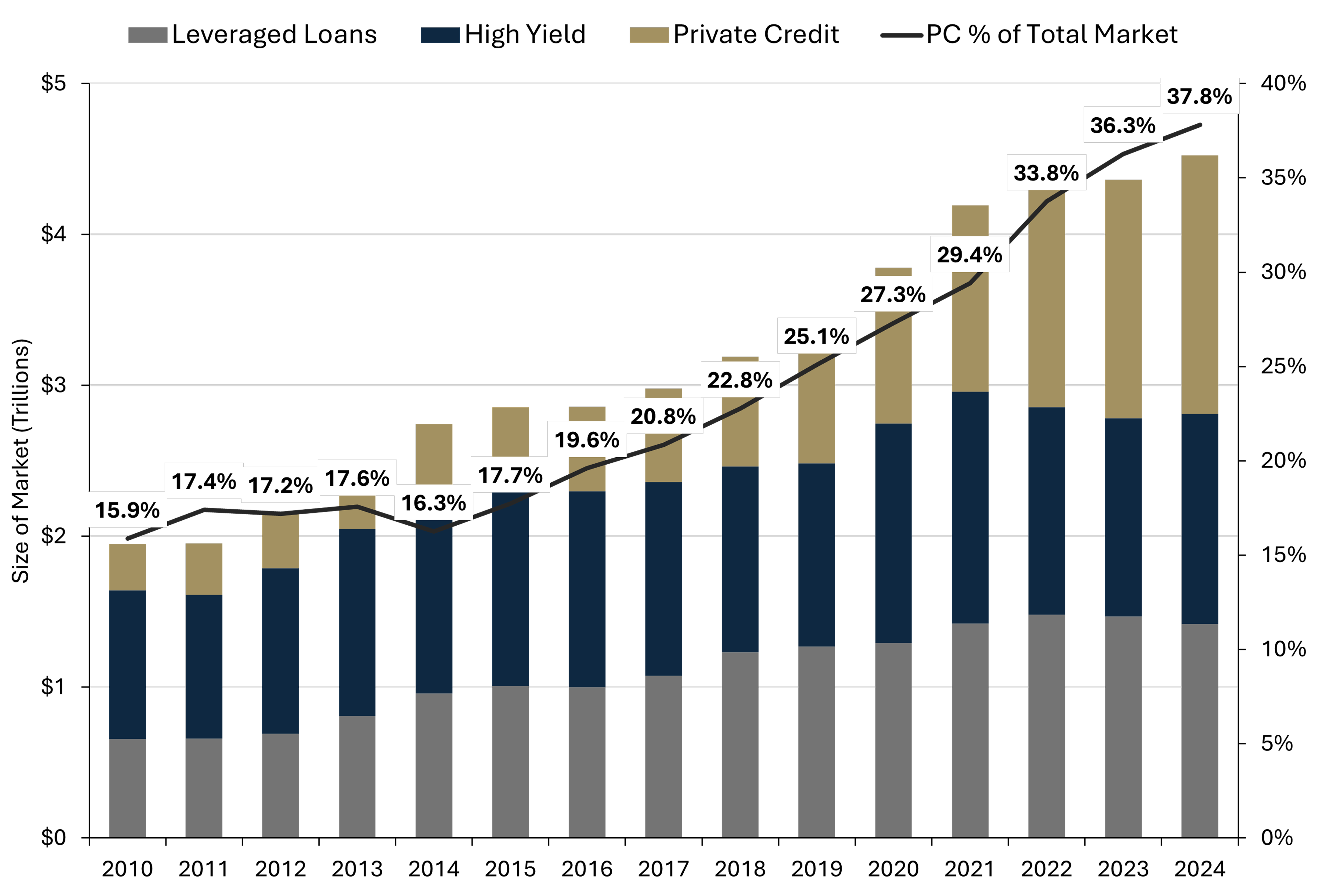

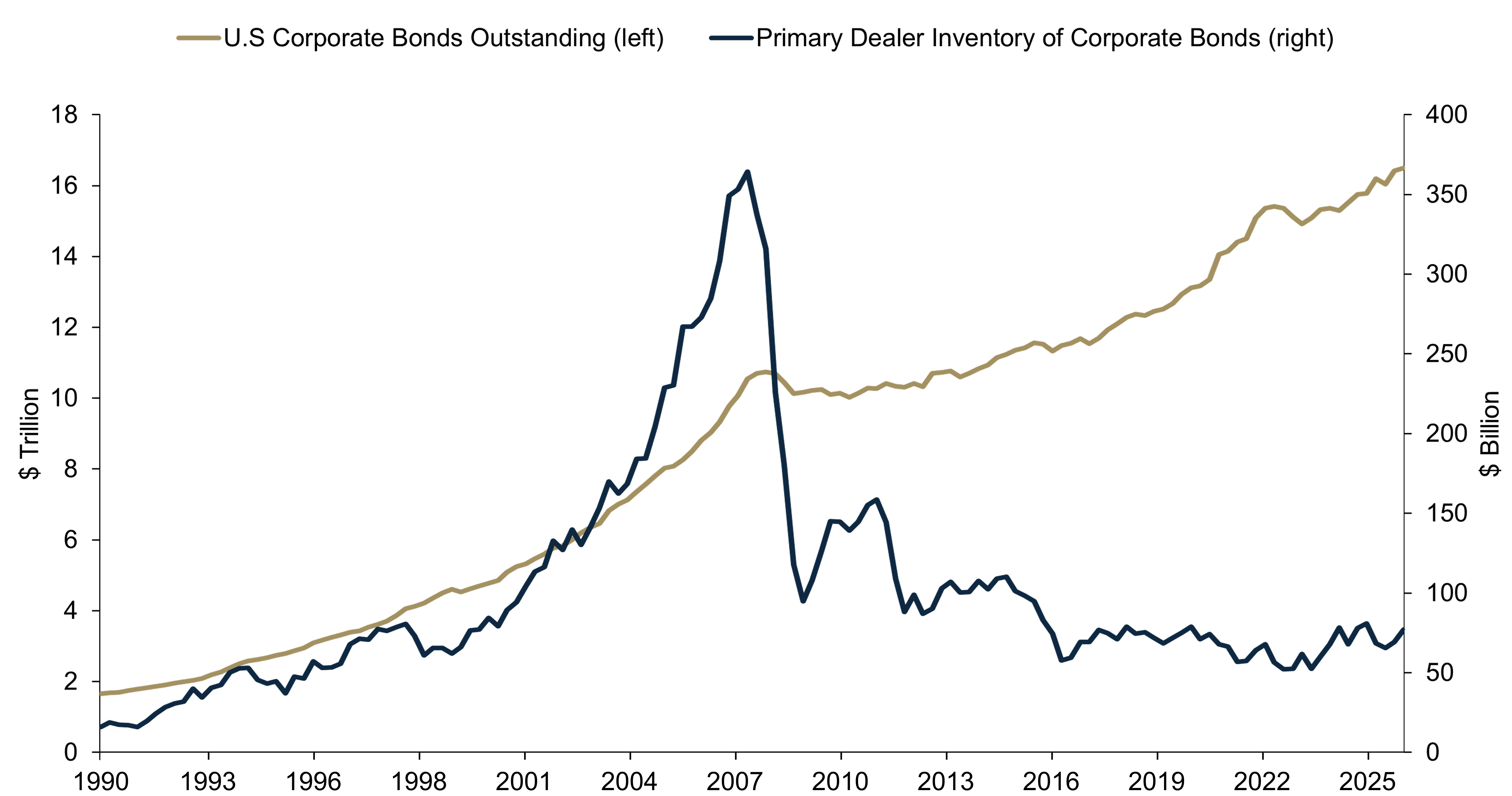

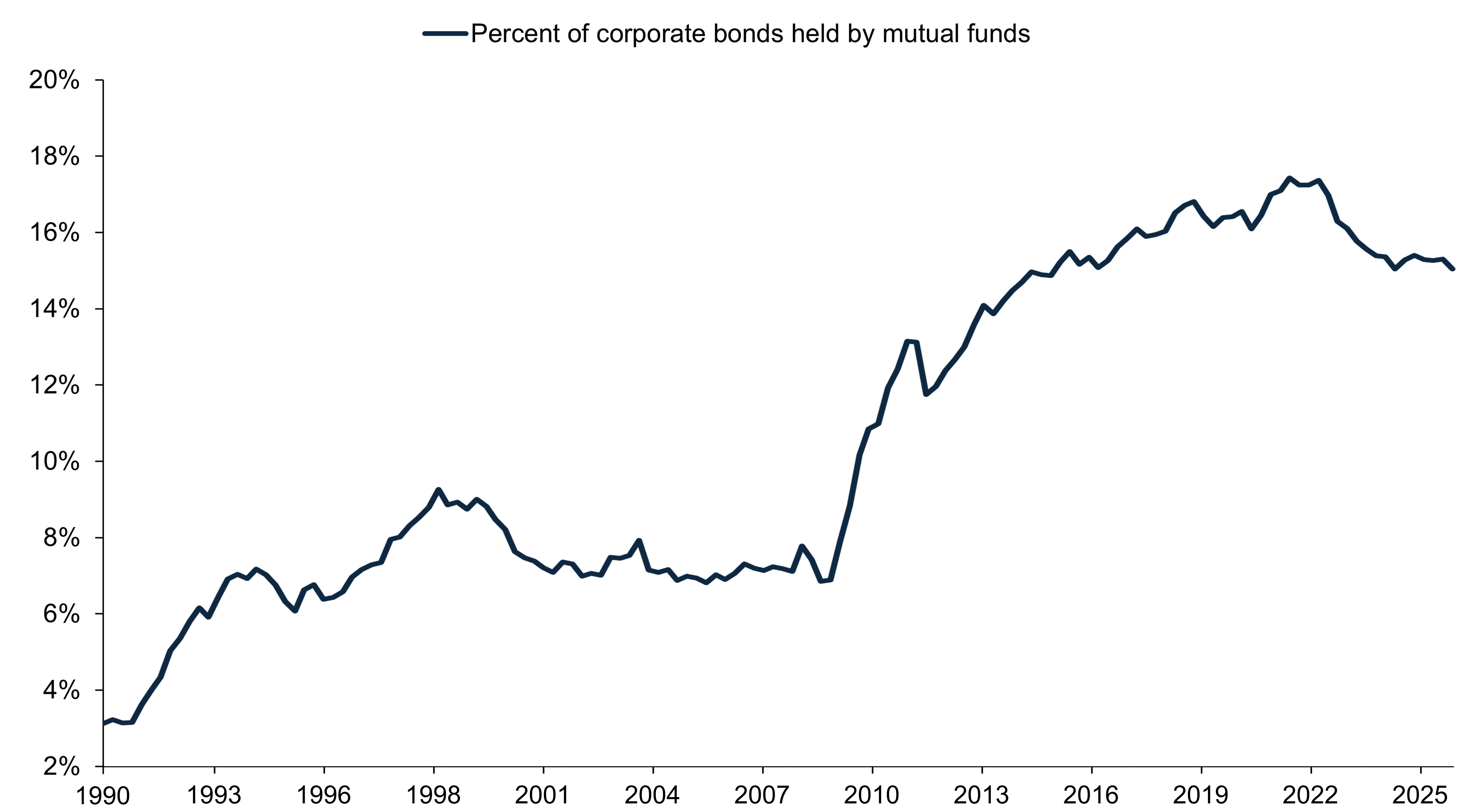

What’s different between 2020 and today is that, while regulatory and legislative efforts globally have limited the amount of risk financial institutions hold on their balance sheets, chiefly through higher capital charges, the impact has been somewhat blunted by a historically prolonged period of low rates. With the ending of ZIRP (zero interest-rate policy) the impact of restrictions, current and proposed, may be more fully felt.

For banks, the implications go beyond limiting further purchases and may extend into outright sales of existing holdings, including those originally earmarked to be held to maturity. Some of those asset sales will take creativity on behalf of buyer and seller and will in many cases be difficult for traditional fixed-income investors to participate in. Taken together, this represents both a curtailment of demand and a meaningful source of potential supply of fixed-income instruments.

Credit Strategies in Today’s Environment

It appears that the current administration may have an appetite for loosening some of the restrictions facing financial institutions, but it’s not clear how likely the changes are or how far they’ll go. What is proposed so far seems unlikely to have a material change in market functioning.

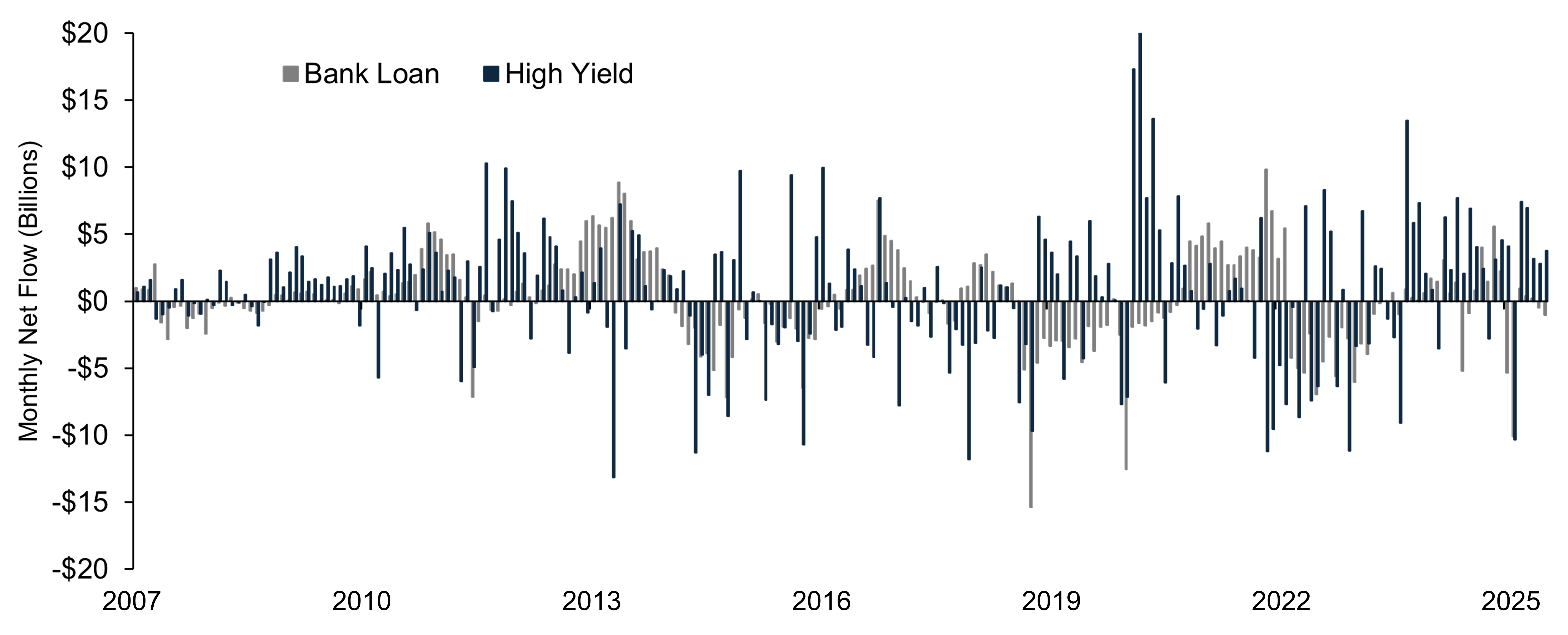

One way to potentially take advantage of this landscape is to do what private credit investors have done—step into the shoes of market actors who have, for reasons already discussed, stepped away. Traded credit offers opportunity as well. With the right structure and the right investors, strategies can provide liquidity to market participants when periods of dislocation or capital shortages occur, acting in a sense as the new risk intermediary.

There are several ways to do this, and there’s no shortage of strategies standing up to try to capture one part or another of this dynamic. Some are focused on pricing dislocations—generally at a market or asset-class level—and offering capital during periods of stress to reap the benefits as markets “normalize.” Others are focused purely on liquidity premiums—building a portfolio of off-the-run instruments and hoping to capture liquidity premiums over time. Each of these approaches has its merits, but they tend to be dependent upon macroeconomic catalysts or sector/asset class-specific dislocations that may be sporadic and limit the opportunity set.

We believe an optimal approach is to narrowly focus on specific instruments, specific investments, and specific stories, while viewing the dislocation as setting the table for opportunity, but not representing the central thesis for investment. The appeal of this investment-by-investment strategy is the broadening of the opportunity set that is evergreen rather than episodic. By focusing down to the line-item level, opportunities within a sector, an industry, an asset class, or a company, become much more frequent. There is also the added benefit of not basing a thesis around a macroeconomic outcome or seeking to benefit from a broad mean reversion within a sector or asset class. Instead, the investment thesis focuses on the specific structure of the security or company. The macro role, again, is limited to being an additional factor toward setting the valuation table.

Credit’s Potential Role in an Existing Asset Allocation

We believe opportunistic credit can enhance an investment program in several ways. First, as a complement to private credit, we believe opportunistic credit is a great fit philosophically, as well as practically. Philosophically, the investor has already allocated to a space, which was also once dominated by banks, to directly capture value. Opportunistic credit strategies allow the investor to step in where traditional holders of risk, such as the capital markets desks at investment banks, or more recently the balance sheets of regional banks, have stepped away or have been forced away by regulatory capital pressures.

In addition to feeding from the same vacuum of competition, opportunistic credit complements private credit in a practical sense because private credit, by design, does not trade or price actively. In contrast, opportunistic credit strategies have an eye toward early monetization of good investments as the investment thesis plays out. While strategies should hold securities that are deemed attractive to maturity, it is also appealing to have the option to realize a gain and recycle the capital into a new idea when the market has caught up to your views.

As part of an overall asset allocation program, credit may also provide diversification benefits to equity risk. Credit has historically diversified rate risk by remaining negatively correlated to rates. In this sense, the role of credit becomes even more significant in terms of earning a strong return but with a lower level of risk than equities, as measured by standard deviation. Credit may also provide access and exposure to different risk premiums and sources of return, especially in a strategy that seeks idiosyncratic opportunities without the constraint of a benchmark. If you think about it simply as “Who gets most of the cash flows?”—for years that was titled toward the bottom of the structure due to the rate environment. That has changed—as noted earlier, possibly for good—if the last 23 years turn out to have been an aberration. With the internal rate of return (IRR) opportunities we’re seeing in fixed-income markets, credit is making a very strong case for recapturing some of the allocation weights it lost during ZIRP.

Summing Up

Our view is that, as part of a credit allocation, an optimal strategy to consider is an active manager with deep credit expertise that can start with a blank piece of paper. Although there is an investment universe dictated by the manager’s resources and experience, in our view a superior approach to credit means not thinking in terms of indexes or buckets. Rather, the investment thesis is about maximizing the return potential for the risk the instrument represents. Today, selection is as important as it has ever been. Properly tailored and situated, we believe it is possible for opportunistic credit to deliver a risk experience in line with traditional index-tracking strategies, while delivering a return experience that is vastly different.